On collecting things:

I try, in my music, to locate and develop the deep harmony between seemingly disparate materials: exotic and familiar, primitive and sophisticated, old and new. Maybe it’s inevitable, then, that to my eye my New York apartment looks like my music sounds. Much of the furniture is contemporary, as is some of the art: but some of both are from long ago and far away. A large black and green abstraction frames a standing 6-foot carved and highly embossed man with a snake wrapped around his feet from New Guinea. (The abstraction is the only art piece in the apartment I made myself. Whatever else you can say about it, it works with the décor, and is beautifully, beautifully framed.)

The sophistication of a lot of “primitive” art fills me with a visceral excitement, and while I don’t own much of the work of the acknowledged 20th century masters, I can see their inspiration in the works that I do own.

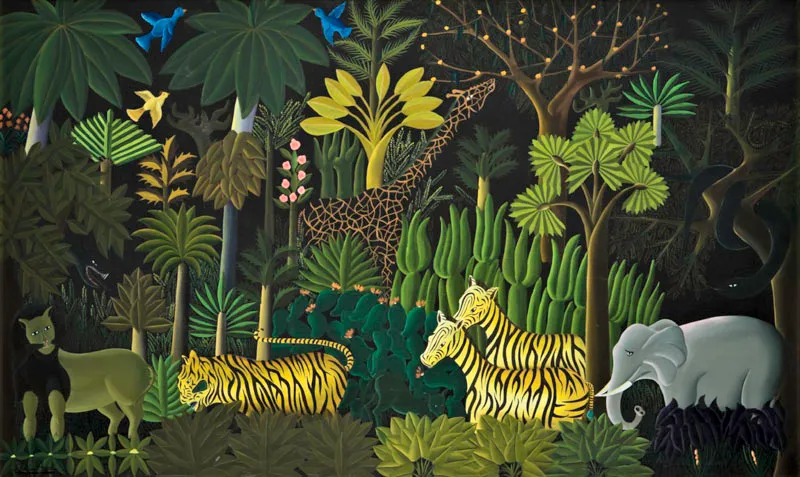

Everywhere in Picasso you can see the same exaggerated shapes, bold, limited colors, and captivating air of comic menace you can see in my New Guinea “canoe mask,” while Braque could have signed his name to my wooden mask with Cassawary feathers from the same area. The thrilling oil The Garden of Eden, by the extraordinary Haitian artist Salnave Philippe-Auguste, owes nothing, and everything, to Rousseau; likewise the Inuit lithograph “Playing kickball with the demons,” of which Miró would have approved. (I like to think the Inuit would have approved of Miró, too.)

Music is everywhere, and, happily, a little of what’s performed is mine: so I get to travel (sometimes more than I’d like) and to look at the art of many cultures. When I see something that speaks to me, I bring it back to join with the family of my other pieces.

So, I would like to tell you about how the various pieces I own came to be. Most of them come from musical trips, but not all.

Two Benin Masks:

Mark Adamo and I had taken our first trip to South Africa in 2002. It is a gloriously varied country, and its arts are fascinating. We were staying overnight at an inn in the Blue Mountains outside of Kruger Park, and wandered into a store backed by a wall of wooden masks. I noticed two large bronze masks in a distant corner, blanketed with dust. When they were cleaned, I was stunned by the minute detail of the bronzework: imagine two noble faces (almost Comedy and Tragedy) each with fantastical creatures perched upon its head. The masks were forged in Benin, in East Africa, a storied port on the ancient Athenian shipping routes: a good portion of the history of the ancient world could be told through a survey of Beninese trade. The masks are enormously heavy and hang side by side in my living room over the mantelpiece, where they harmonize effortlessly with the Art Nouveau scrollwork over the (erstwhile) fireplace. They were created as guardian images for temple doors in the middle of the 19th century.